Ran review by The Grim Ringler

In the halls of filmdom there are very few film directors that can be said to have affected their own films, let alone the way that other people make them. There are a few directors though that are so visionary and so talented that they make films that manage to transcend the limitations of the screen and touch the very souls of the viewers, and these are the directors that become the greats, the ones to be studied, stolen from, and emulated. Then there is Akira Kurosawa, a man whose talent and eye for the beauty of the macabre created a legend that shadowed him to the last of his days. Sadly though, Kurosawa isn’t nearly as well known as he should be in America and that’s a shame as his movies are the kind that movie fans insist rarely get made – things of such dark beauty that each seems like a new and wondrous dream unto itself. Kurosawa is considered by many to be, if not the greatest filmmaker the world has known, then to be in that small, small group of people, and that my friends is not even the half of it. A Japanese director, Kurosawa brought the age of the samurai and feudal Japan to the age of Shakespeare, creating several Shakespeare adaptations that melded the works of the bard with an era that we Americans still know very little about. In Ran Kurosawa takes on King Lear and in so doing has created a film of war, family, and betrayal that is as haunting as anything you may see.

Ran is set during the age of Feudalism in Japan and finds a father and King, the aging Lord Hidetora, ready to step down from his thrown and give it to one of his three sons. He has called for a hunting party filled with his allies and friends and has chosen this time to step away from his position but when the son he has chosen to take his place refuses the honor, Hidetora flies into a rage, fueled by the flattery of his other two, more power-hungry sons. Hidetora, refusing to listen to the advice of his councilor, banishes his son, damning him for his impudence and his refusal to honor his father. And the son, unable to understand what is happening and sensing the treachery in his brothers, leaves his father, heartbroken, banished and alone. The councilor too is banished from the site of the King and all that remain are the yes-men and the two scheming sons. Hidetora thus gives the next oldest son the lordship under the stipulation that he shall always be welcome at either son’s palace and will still be held in a place of honor. The sons both agree to this and the matter seems to be settled. But as Hidetora eases into a civilian life again he quickly becomes a burden on the son that has taken the lordship, the son’s wife (a woman who has lost her family to the treachery of Hidetora and whom must now live in the castle of her father as the wife of her mortal enemy’s son) insisting that the former lord is still acting as if he himself is the king and needs to be dealt with. Unwilling to compromise his behavior, Hidetora leaves his son’s castle and rides out with his bodyguards to the castle of his other son, arriving only to be told that his caravan of guards must stay outside the castle’s walls by order of the king. Infuriated, Hidetora refuses to stay, angered that his sons are treating he and his warriors this way, so he sets out for the last castle in the kingdom, one that has been all but forgotten and which he feels should belong to him. The new king’s wife though sees this as an outrage, as a complete affront to the power of his son, and so she presses her husband to join with his brother to put the king out of the castle. And as the war against Hidetora rages, his men dying by the dozen as they protect their lord, Hidetora’s mind shatters and though he escapes his death at the hands of his sons (one of whom is murdered by the other in a play for power), he walks now in a nightmare world, re-living every evil act he has committed and unable to free himself of these walking dreams. Meanwhile the son that had always loved and stood by him hears news of the treachery that has happened and gathers an army to find his father (who is wandering the countryside gibbering, shadowed by his fool, the only person to see through everything that has happened and to speak the truth of it) and setting up a final battle pitting brother against brother, army against army, with Hidetora, their mad father in the middle, haunted by the ghosts of his own villainy.

Sadly, there is no way to describe Ran and it’s scenes of war in a way that can convey the horrific beauty of what you are seeing. In the most elaborate and haunting scenes, when Hidetora’s castle is under siege and his men are being massacred, there is no sound, there is no dialogue, there is just a beautifully done musical backdrop that is a chilling contrast to the bloodshed we are seeing. A score that sounds almost as if it is the very sound of far off gods mourning the bloodshed they are seeing. And while no film can yet rival Saving Private Ryan in terms of its battlefield brutality, Ran certainly stands very closely to SPR in terms of its outright feeling of numb wonder you get as you watch hundreds of soldiers (a feat that few directors could ever accomplish and that has yet to be rivaled today) storm and take a castle, devouring everything that stands before them. The power of the film comes too in the performances, which though may be in a language foreign to Americans, which are so strong and full of such pain and anguish that they themselves become ghosts, doomed to their fates because it is all they know. Doomed to blood for it’s all they can see. Ran is filmed as if it’s not a film but a play, the action not filmed as modern-day action is, with roving cameras and pointless pans and zooms, but with slowly arcing crane shots and closer shots to show not the grotesque beauty of war but the sickening carnage as these people’s worlds fall apart. The most striking example of this being when Hidetora walks in on two of his concubines as they are kill one another so they don’t have to go into the service of another man, a third woman preparing to kill herself as her Lord leaves the roomed horrified. The film, to be fair, is very long, and the fact that it is a foreign film doesn’t make it any easier on the casual viewer, but if you let yourself get taken into this world you will find that the language of the film matters less than the feeling the images portray, sweeping the viewer up into a world we had only read about at best.

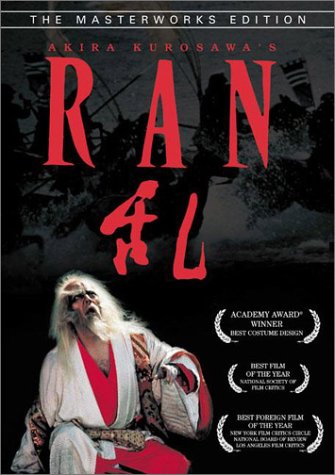

There are two dvd version of Ran out and I heed you to beware if you choose to purchase it. The first release of the film was notorious for its mediocrity but that has since been remedied by Studio Canal, who has released a gorgeous special edition of the film that looks and sounds as clear and crisp as it deserves. There are two commentaries to the film, each one as much about the director as they are about the film but both very well done, if a bit dry. The picture and sound though are the standouts here, even when played on very high end equipment, which just makes the film shine all the more.

I am sure many will find flaws with Ran, and as with any film, I suppose it is not perfect, but the fact remains that there are very, very few films as brilliantly made, as thoughtful, and as darkly wonderful as Ran. It stands shoulder to shoulder with films like Citizen Kane as cinematic perfection that shall stand the test of time with ease. Made almost like an opera, the music as important, if not more, than the words the characters are speaking, Ran is not a film to see, or to study, but to experience. To watch and let take you where it will. Ran is not just a good or great film, it is art, pure and simple, and is a film any fan and scholar of film needs to see.

10 out of 10 Jackasses blog comments powered by Disqus

Search

Ran

IMDB Link: Ran

DVD Aspect Ratio: 1.85:1

DVD Extras: commentary, trailers, restoration demo, a pencil and notepad to take copious notes