I Now Pronounce You Chuck and Larry review by Rosie

I Now Pronounce You Chuck and LarryUm, … am I the only one who sees where he’s going with all this? I mean, I wouldn’t think that I could possibly be the only one who sees where this is heading, but since I haven’t heard anyone else mention it I just have to ask: doesn’t anyone else see where Adam Sandler is going here? No one. That’s your story. That’s what you expect me to believe. Ok, let’s just step back and take a look at the big picture here for a minute:

1995: Billy Madison – Adam Sandler steps onto the scene with a low-brow, high-comedy classic that takes dead aim at spoiled, lazy rich kids (easy target, sure, but a safe way to start bringing people into the fold.) Still though, even now he begins testing the water carefully with a few playful jabs at the slightly more sympathetic kids and teachers in the movie.

1996: Happy Gilmore – Sandler is still careful to have his own, generally unsympathetic or vulnerable, character take the brunt of the abuse but sends up a few more test flares with a couple of sucker punches tossed out at amputees and the elderly.

1998: The Waterboy – With the preliminary results for his formula (more on this later) showing great promise, Sandler commits to his first full-scale test. In his first release without the safety on (i.e. without an arrogant jerk main character as the main focus of the abuse to justify the collateral abuse of more sympathetic characters), he takes dead-aim at the mentally handicapped and peppers in a few good shots at jocks, southerners, and the home-schooled just to really see where he’s at so far. Results are somewhat mixed, but still positive: not quite as much adulation as the previous tests but still no significant blowback. Overall, very good news considering the inherent risk of “going live” for the first time.

1999: Big Daddy – Knowing not to get too greedy too soon, Sandler dials it back just a little but still keeps everyone moving in the right direction with a lightweight satire of single mothers, deadbeat dads and unwanted kids.

2000: Little Nicky – Sandler gets a little cocky, reels back and catches the devil flush with a full-on haymaker. Initial results again seem to be positive, though some eventual repercussions for this one may still be pending.

2002: Eight Crazy Nights – On the advice of Trey Parker and Matt Stone, Sandler tests the hypothesis that you can make fun of anyone and anything in any way you want as long as you do it in cartoon form. Still not being totally certain about this, and not wanting to destroy all the work towards his goal that he’s done so far if anything goes wrong, he decides to test the hypothesis by making fun of a religion but play it somewhat safe by just attacking his own. Despite promising results, Sandler decides it’s just not as fun to have to hide behind animation and decides to return to what he knows.

2002: Mr. Deeds – As part of Sandler’s twenty-year chess game with America, he makes a carefully plotted move that quietly begins to establish him in the “remakes” game. Though its significance remains largely unnoticed even to this day, history one day will regard this as the shrewdest example of his calculating nature.

2003: Anger Management – Still not above tweaking his formula at this stage to ensure success down the road, Sandler experiments with the idea of using a gigantic star to diffuse some of the focus on the content and incorporates Jack Nicholson in a story that makes fun of people trying to get help for their problems through counseling and support groups, as well as the doctors trying to help them. Results indicate that public reaction to content is not significantly different enough from previous efforts to justify the additional cost in salary of this approach.

2004: 50 First Dates – Sandler reconfirms original formula with a little throwaway piece making fun of amnesia victims and Hawaiians.

2005: The Longest Yard – Sandler turns up the visibility another notch on his penchant for updating classic movies with edgier remakes. With the end game now coming into sight over the horizon, he makes the move here to merge the two streams he has been cultivating for a few years now by infusing the remake with a healthy dose of the kind of politically incorrect racial and sexual orientation humor that he’s been gradually desensitizing audiences to in his other movies since the beginning now.

Which brings us up to 2007’s I Now Pronounce You Chuck and Larry. Since technically this is the movie I’m actually supposed to be reviewing here, I’ll deviate from the history lesson for a moment to actually do that. But keep in mind what I’ve just showed you as you think about this movie, and if you still don’t see where all of this is headed when all is said and done, well, you probably deserve what you’re going to get.

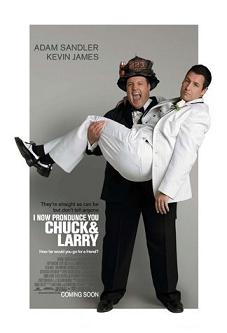

Chuck and Larry stars Adam Sandler (Chuck) and Kevin James (Larry) as two New York City firemen who find themselves in a pinch after a bureaucratic loophole leaves single-dad Larry unable to have his life insurance benefits transferred to his kids after his wife passes away. After a close call on the job reminds him that he can’t afford to wait for the issue to be resolved on the city’s schedule, he convinces best friend and confirmed bachelor Chuck to sign on to a civil union with him so that Chuck can receive the benefits and take care of Larry’s kids should anything happen to him on the job. Chuck reluctantly agrees to go through with it on paper, but when a suspicious state fraud investigator (Steve Buscemi) begins to turn up the heat on them, Chuck and Larry have to continue upping the ante and live more and more openly as a gay couple to avoid losing their jobs and going to jail on an insurance fraud rap.

As a pure comedy, Chuck and Larry is what it is. Steadily amusing, occasionally pretty funny, ultimately wrapped up with an everybody-is-redeemed bow on top. But as a progressive step towards Sandler’s ultimate goal, it is an important landmark. I mentioned earlier that Sandler has a formula which he has been tinkering with here and there with every movie (trying things like the big stars, the sympathetic vs. unsympathetic main character, the animation, etc.). These are all understandable adjustments to try, as he cannot be too careful before attempting his ultimate goal, but at its core the formula has remained virtually unchanged since the beginning. And in this day and age of unreasonable, panicky, reactionary political correctness - the kind that claimed so many innocent careers at CBS and MSNBC in the infamous Nappy-Headed Holocaust of 2007 – the effectiveness of such a simple little formula is really quite brilliant to consider.

Known among a handful of the world’s top media analysts and sociologists as Adam Sandler’s Forcefield Formula (ASFF), the formula dictates a few simple ways that Adam has pioneered for being able to make fun of any vulnerable minority or special interest group in America with virtually zero repercussions from anyone for doing so. Without going too much into the mathematics of it, there are four key pillars of the formula that anyone attempting to understand the bigger picture of his career should be aware of: justification, diversification, misdirection, and redemption.

The first pillar, justification, simply mandates that whatever socially offensive actions any one character participates in, whether it be just for one cheap joke or the foundational plot of a whole movie, the character’s participation in this type of behavior must be driven by a larger motivation that justifies what they are doing beyond just making fun of people. For example in Chuck and Larry, the characters justification for acting out what is otherwise fundamentally a two-hour gay minstrel show is the caveat that they are only doing so to try to protect Larry’s two innocent little baby kiddies from being snatched up and thrown into the foster care system by the big, bad, unreasonable government if anything were to happen to Larry. And the fact that they’re idea of pretending to be gay means prancing around and shouting things like “Yeah, we totally love to listen to Barbra Streisand and do it in the butt all day.”, well, we can forgive them because they’re just a couple of regular Joe Six-packs who got forced into this situation and just don’t know any better. (And in the back of the theatre, from behind the glass, Adam Sandler looks down past his cigar and over the crowd, and smiles to himself.)

Diversification, the second key pillar, just requires that the abuse be somewhat spread around. So, if he wants to make a movie where he can use all his favorite eighth grade baseball camp gay jokes, that’s fine. Just pepper in a couple jokes at the expense of a few other identifiable groups (occupations, religions, ethnicities – doesn’t matter who) so that it doesn’t seem so much like you’re singling out the group you really want to lay into. As long as you can defensibly argue that “everyone gets it” in this movie, you can feel confident that you have satisfied the threshold for diversification.

Misdirection is a pretty standard tool in a lot of genres, but a definite requirement for using ASFF correctly. Simply put, this is the inclusion of a running subplot that is equally as (if not more so, to some people) compelling as the main story containing the satire. Adam’s misdirections almost always come in the exact same form: the ongoing, boy-meets-girl, will-they-or-won’t-they, heterosexual puppy love subplot. The genius here is not in the idea itself, but in Adam’s virtuoso command of how to use it. No one pulls off the use of an ooey-gooey love story as misdirection better than Adam Sandler. For the hopeless romantics (i.e. 80% of his female audience, 20% of the men), he baits the hook and reels them in with fluid ease of Neptune himself. And for the less sappily inclined, whom a lesser misdirector might decide to just not worry about, Adam picks up the spare by incorporating the most unfathomably, impossibly attractive women into every love story to help distract everyone left in the room (i.e. reverse those other proportions). By the time the movie’s over, the whole audience is too busy processing through their particular fantasy (either of a guy who treats them/talks to them like sweet, fumbly, goofy Adam or a girl that looks like Bridgette Wilson/Julie Bowen/Fairuza Balk/Joey Lauren Adams/Marisa Tomei/Jessica Biel/insert name here) to remember anything they were supposed to be offended by.

The final, and most important pillar, is redemption. The redemption here is not necessarily of the main character, but of the group being most made fun of. The importance of this element can not be stressed enough – it doesn’t have to be realistic or even reasonable, it just has to be there. Even the most superficial redemption of the group being targeted that somehow comes as a result of all the abuse they take throughout the movie is enough to completely forgive all of that abuse in the minds of most audiences. In Chuck and Larry for example, the two hours of manipulation and satire of the gay community is completely wiped away by the inexplicable final few scenes where the entire gay community comes out to support Chuck and Larry and hail them as great, if not misguided, heroes who taught everyone a lesson about what true love really is. The fact that they inspired a few side characters to come out of the closet and be proud to display their cartoonishly flamboyant new gay pride adds further to the redemption. This kind of throwaway bit of redemption is a virtual get-out-of-jail free card that has been a staple of Adam’s formula from the very beginning now. Go back to any movie that he was involved in the writing or production of and you’ll find almost everyone ending the exact same way: an explicit redemption of the most targeted group, and then a return of the entire cast of characters from the whole movie to each be seen in one final shot either dancing, kissing, singing, or anything else to convey with that last image that, despite any lampooning or abuse they took throughout the entire duration of the movie, they are all happier and better off for it now. All is forgiven in the audience and Adam Sandler remains Hollywood’s Teflon Don.

(And, just as a quick aside, let me be absolutely clear here – I LIKE where Adam is going. I like what he is doing and I am a big fan. Not because of any ill will towards anyone, but because I think he also has no malicious intent towards anyone except for the politically correct busybodies who think that the world needs them to let everyone know when to be offended and needs their help to save the innocent, little kiddies from hearing someone say the s-word on TV before they have a chance to learn about swear words the right way at home, by hearing their parents screaming them at each other from downstairs while laying curled up in a ball under their Kung Fu Panda bedspread trying to make it all go away. These self-appointed media meter-maids are the real target behind Adam’s grand plan, and why I applaud it even more now that I can see where he’s going with all this. He’ll have them all right where he wants them when he lowers the boom – stuck between having to either bite their tongues and just let him get away with it, thereby undermining their credibility in all future efforts to play the morality police, or trying to do something about it and having to explain why none of his other many, many targets over the past decade plus were also worth their efforts. Check and mate on the windbags and hypocrites. Brilliant!)

So now that you know the formula, and now that you’ve stepped back to look at the big picture, are you still really going to try to tell me you don’t see where this is all headed? You’ve seen the progression – slowly warming audiences up for it by gradually targeting more and more politically dangerous targets. You now know the formula – tested and retested successfully for all possible chinks in the armor. You’ve seen the groundwork being laid – Adam building up his credibility with the studios as someone who can get remakes of old movies greenlit and turn a profit on them. And if you see Chuck and Larry, and watch what he does with the casting of Rob Schneider as the “Asian Minister” (which basically consists of several scenes of him taping his eyes back with scotch tape and saying things like “Ohhh, herro theah Chuck and Rally. So, you want to get mallied? What kind of celemony you rike? You want my daughter to thlow some shlimp flied lice for you outside the door? Wha’eveh you rike, we can do. Just fi’ hunled dorrahs.” … etc.), you know that he’s beginning to feel his oats a little more in the racial department. And you really want me to believe that you have no idea how this might end.

Well, if that’s your story that’s your story. If you want to get all huffy and puffy when this goes down, making a big scene about how outraged and offended and appalled-at-such-a-thing you are for all your neighbors to see, I suppose that’s your choice. But you better start thinking now about how you’re going to explain away all the times you’re already on record as having enjoyed these other movies he’s been setting you up with all along.

And you can’t say he didn’t warn you.

--

Updated Postscript: Let it be noted that the preceding review was completely written and posted (elsewhere) a good two months before any advertising campaigns even began (or at least any I was aware of) for Sandler’s latest project, the Middle Eastern minstrel show You Don’t Mess with the Zohan. Though I haven’t actually seen it yet, I feel confident enough from just what I’ve seen in the commercials to predict that it conforms exactly to the aforementioned formula. Vindication, baby.

7 out of 10 Jackasses blog comments powered by Disqus

Search

I Now Pronounce You Chuck and Larry

IMDB Link: I Now Pronounce You Chuck and Larry

DVD Relase Date: 2007-11-06

DVD Aspect Ratio: 1.85:1