Rescue Dawn review by Rosie

Rescue DawnRescue Dawn is the best movie I’ve seen in years – and it’s not even close. Of course I’m going to have a little explaining to do to make a case for such a bold statement, but I just wanted to put that out there right up front for anyone who doesn’t read this all the way through. For a movie to wear such a heavy crown and still walk upright, it’s got to be strong in every part of the body. So the best way for me to lay out this case is to break it down piece by piece and prove that I’m not crazy and you, if you disagree, are.

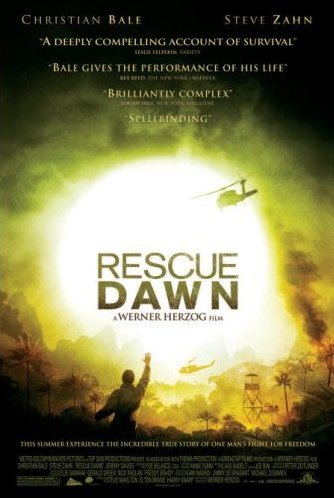

Story: In the early stages of what would become the Vietnam War, U.S. Navy pilot Dieter Dengler (Christian Bale) survives being shot down only to find himself alone and being hunted through the living jungles of Laos by a Pathet Lao militia. After managing to evade them for a while, Dengler is eventually captured and ultimately brought to a prison camp to be held with a handful of other U.S. and Thai P.O.W.s. There he meets Lt. Duane Martin (Steve Zahn), “Gene from Eugene” (Jeremy Davies) and a collection of other memorable characters. With their help, Dengler hatches a plot to escape the prison and find their way out of the jungle. Dengler’s evasion, capture, imprisonment and escape are made all the more fascinating by the fact that the whole story is true.

In fact, unlike so many dramatizations “based on a true story”, the central focus of this story all the way through is its realism. To the point that there are even some moments that didn’t make sense to me at the time I was watching it, but made perfect sense when I went back later to read more about the real story. And I’m guessing, based on a few scenes that drew isolated laughs from a few older, retired military-looking guys in the theatre, that even the minor details of Navy life in the late 60’s is insightfully accurate.

Director Werner Herzog originally brought Dengler’s tale to the screen in the 1997 documentary, Little Dieter Needs to Fly (which, you can be sure I just rocketed to the top of my Netflix queue and will be following up on soon), and by several accounts I have read even left out some of the more sensational aspects of Dengler’s experience from the current version. As a rule I generally don’t give a movie credit or criticism for story quality when it is a documentary or based on a true story, but that should not take away from the fact that this happens to be a fantastic story that needed to be told.

Directing: I’m not even going to pretend that I’m at all familiar with Werner Herzog’s apparently illustrious catalog of work. I’m a thoroughly ethnocentric fan when it comes to movies, and I feel no need to apologize for it. All I know about him is he also directed Grizzly Man - which was at least half already directed for him, by that loosely closeted psychopath that it’s about, before Herzog even got involved. But with his most recent effort, I know all I need to know about him. Herzog is a master craftsman and has woven together one of the tightest, most gripping and human tales seen on-screen in a while. Opening with a hauntingly beautiful ride over the firebombing of a Laotian countryside, the manipulation begins right away – drawing the audience in and then letting them back out again, at will. Throughout the film Herzog repeats this cycle, drawing the audience in so slowly they don’t even notice, until he turns them back out and they realize for the first time that they are nearly up off their seat or clutching the arm next to them. Along the way he effortlessly throttles the audience back and forth from rapt attention to refreshing laughter and back, again and again.

As deftly as the story is told, the cinematography supports the whole film as much as anything else. I don’t know much about the technical lingo that paid professionals and geeks might bandy about over soy milk lattes and Mountain Dew, but whether it was done with lighting, camera lenses, film quality or a time machine, Herzog creates a film that doesn’t just look like it is set when it should be – but as if it were actually made at that time as well. The lack of any backlit moments or glossy finish to the final product is an effective touch to help transport the audiences back in time with the characters. I’ll probably return to Herzog and drool all over his sandaled feet a little more in the Effects section, but I think you see what I’m getting at here. Basically, if Herzog were directing this review, it would be half as long and twice as good.

Acting: Before this movie was even on my radar, it was already beyond any possible debate in my mind that Christian Bale is among a handful of absolute, all-time great actors who we are fortunate enough to be witnessing in their early-to-mid primes. For the record, Matt Damon, Johnny Depp and Djimon Hounsou are the others. A few of these actors, and maybe a couple I forgot, could be reasonably debated as to whether they belong or not on that list (though I can make a slam-dunk case for all of them). Bale is not one of them – there is no possible rational argument that he doesn’t belong high on that list. Period. End of conversation. But I don’t plan on laying out an argument about anyone’s place in history right here, I mention that only to say that Bale’s was the only performance I expected to be worth the price of admission in this film. Predictably (and I mean that as a compliment) it was, but the rest of the cast came out swinging as well.

The one guy who I was worried would be a distractingly weak link was Steve Zahn, but as the barely-holding-it-together prisoner Duane, Zahn raises his game to a whole new level. And after more than a decade of truly annoying performances, let’s hope he figures out how to keep it there. But the guy who absolutely killed it in this one was Jeremy Davies. Davies delivers a perfect performance as “Gene from Eugene”, capturing the essence of so many war-ravaged, disillusioned, living casualties of Vietnam that still occupy bar stools and shelter cots in every state today, and offering viewers a tangible glimpse of how they could ever have come to be. The dedication he brought to the role shows in his emaciated body (perhaps a little personal nod to his co-star’s now famous similar effort for The Machinist). It’s hard to gauge right now how much attention this film is getting in different circles, but there cannot be five better performances for Best Supporting Actor nods than Davies’ in this, and it would be ridiculous if he somehow gets snubbed.

Though these three performances are the most central and noteworthy, there was not a weak link in the entire cast. Without a word of English, every Vietnamese guard, soldier or villager conveyed distinct, authentic characters that give the story great depth and balance.

Effects: Or should I say lack thereof. Credit Herzog again here for knowing that less is more. By taking out the artificially amplified gun blasts and explosions that have come to define the way that we, who have never actually been to war, have come to imagine war Herzog puts the audience into an authentic environment that he knows needs no special effects to explain itself. What other directors would have indiscriminately peppered with exaggerated land mines, wrenchingly melodramatic deaths and loud chase music, Herzog lets speak for itself. One scene in particular brings this into focus strikingly, as we watch helplessly while Dieter is being chased across an overgrown Laotian landscape, with nothing more than a panning, wide-angle shot capturing the quiet reality of it.

This, ultimately, may be the greatest compliment I have for this film. After more than thirty years of Vietnam movies and shows of all conceivable kinds, Herzog and his cast and crew have managed to deliver an original look at a time and place in history that most of us have never seen this way before. He reminds us that life in Vietnam was not a constant carousel of explosive battles, emotional exchanges and 60’s rock montages. He reminds us that the quiet, patient, effortless brutality of the jungle can be far more scary than watching a matinee idol wrestle an alligator over a waterfall. He reminds us that when people die in war, they usually don’t die with teary-eyed final words – they just die.

Disclaimer: I’m sure you will read plenty of critics who find plenty of nits to pick with this film, as they feel morally and contractually obligated to do with every film. The disclaimer here is that I have never thought of myself as a movie “critic”, and neither should you. What I am is just a movie fan who has the privilege of writing about the movies I see. Some might be embarrassed to gush so unapologetically about a movie, or might presume I’m not well-versed enough to recognize any flaws it may have. No, I saw all the same tiny, irksome details that others may choose to pounce on. But, as a fan, it is very few and far between that I ever see a movie anymore that has me walking out, legitimately unsure of whether it had lasted four minutes or four hours. Plus, if you’ve ever read any of my other reviews, you should know by now that I feel no obligation to offer a balanced perspective on the movies I hate, so I figure it should work both ways.

10 out of 10 Jackasses blog comments powered by Disqus